The Kitchen Sink Painters were a group of British artists who made artwork depicting scenes of everyday life. The term ‘Kitchen Sink Painting’ was invented by art critic David Sylvester as a way to deride their work which he critically characterised as; “An inventory which includes every kind of food and drink, every utensil and implement, the usual plain furniture and even the babies’ nappies on the line. Everything but the kitchen sink – the kitchen sink too.”

But what’s wrong with painting the kitchen sink? Artworks based on direct observation are a useful insight into what an artist is seeing, thinking and feeling at the time. They might also tell us about the intimate details of an artist’s life and act as a valuable record of the social and political context.

‘Still Life with Chip Frier’, 1954 by artist John Bratby is a great example of ‘Kitchen Sink Painting’. It is a celebration of object and form in paint. The painting was made with oil paint on hardwood. The work depicts what looks like most of the contents of the artists kitchen laid out on a dark brown table. It’s an epic still life which buzzes with a light-hearted energy. Importantly it offers a glimpse into the artists reality.

‘Still Life with Chip Frier’, 1954 by ©John Bratby

Art exploring domesticity has a long-standing tradition in art history. Whether it’s a picture of the bedroom of an aspiring modern artist or an artist’s view of their own feet while being in the bathtub, artists have taken inspiration from their domestic surroundings.

The subject of domesticity continues to be an important theme in contemporary art. Here I’m going to look at a few key examples of contemporary artworks which explore domesticity in different ways.

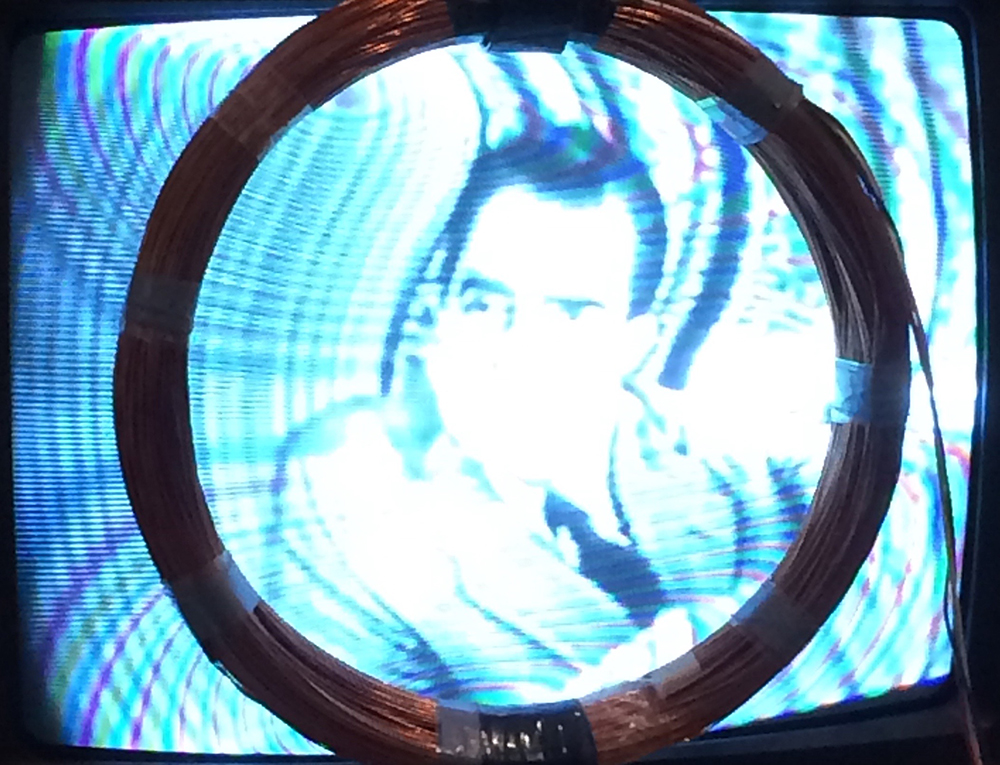

‘Seizure’ © Roger Hiorns

‘Seizure’ by artist Roger Hiorns was originally commissioned by Artangel in 2008. The artwork transformed an empty council flat in Southwark, London into a cave of beautiful, blue copper sulphate crystals. 75,000 litres of liquid copper sulphate were used to cover the entire flat in crystals. Domesticity was transformed into a sparkling fantasy. The work is now housed in Yorkshire Sculpture Park.

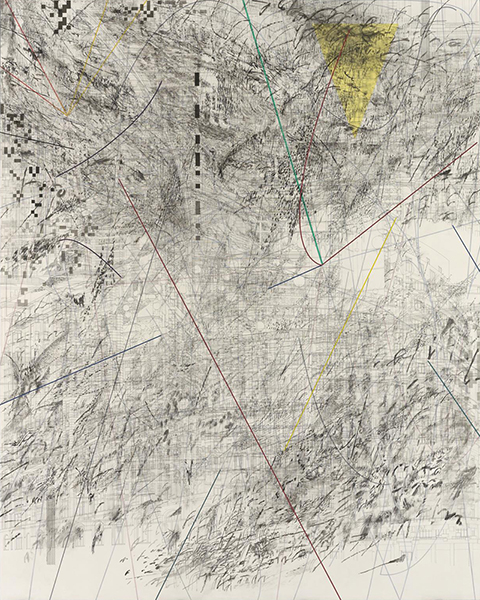

‘Hubris’ 2012-13, oil on linen backed with sailcloth 320 x 230cm © Nigel Cooke

The painter Nigel Cooke plays with the conventions and traditions of still life painting in his work titled, ‘Hubris’ from 2012-2013. The painting depicts a group of objects piled up on a hill which are overlooked by a bright yellow, geometric modernist building. The objects are specifically selected to mimic and parody the conventions of still life painting. The prosthetic eyeballs, glasses, books, fine fruits, golden watch and fried egg are grouped together to represent a loss of creative confidence. This could mean the artists own struggle with creativity or with the conventions of painting and art itself. A faint figure in the distance can be seen poring out paint in the distance.

‘After Lunch’ 1975 acrylic paint on canvas © Patrick Caulfield

‘After Lunch’ by Patrick Caulfield combines different styles of representation to create a new picture. The painting depicts the inside of a restaurant in a bold, graphic style. The image is stylised and even a waiter is reduced to a few bold outlines as he overlooks the inside of the venue. Most of the scene is created with straight black lines on a flat blue background except for one section within the picture. This rectangular section depicts a landscape scene in a photo realistic style. The contrast of styles creates a tension. Our gaze is drawn to the landscape section even though we know it is no more ‘real’ than the rest of the picture. This play between interior and exterior creates an ambiguity which leaves us questioning the depiction of reality in the picture.

Find out more; https://www.tate.org.uk/art/art-terms/k/kitchen-sink-painters

Read more blog posts; https://contemporaryartprojects.art.blog/blog/